The deglobalisation phenomenon has taken root since the outbreak of armed conflict in Ukraine. Spiralling inflation has taken on unprecedented force along with it since the Russian invasion and has become public enemy number one for central banks, governments, businesses and households alike.

In the absence of any confirmation of whether there will be a decoupling of trade blocs, a sort of economic Cold War between the US and China – a grey area that Russia is joining – or just a rearrangement of the driving forces of the sacrosanct liberal principle of unrestricted flows of goods, services, capital and professionals and workers, with a reconversion of value chains, logistical channels and international financing conditions and payment systems, market diversification is still a pattern that is not risk-free. Because neither geographically nor sectorially do attractive business niches appear at first glance to consolidate corporate investment strategies that require, more than ever, permanent geopolitical and economic-financial analysis.

Ignacio J. Domingo

The war in Ukraine is resetting international trade and investment at a pace and intensity that could have hardly been predicted before the Covid-19 pandemic, although it became easier to foresee since the outbreak of the armed conflict in Europe. Disruptions arising from the social confinements and economic hibernation during the Great Pandemic have resulted in more demonstrations of resilience from businesses and markets and spawned public enemy number one: inflation. So much so, that the flow of merchandise, services and equity has been disturbed and has seriously hindered European car makers, Georgia or the Maldives hotel owners as well as Bankok’s or Lima’s manufacture centres and has overall impacted consumers violently due to the cost increase in the energy, food and other commodity industries, in particular metal commodities. Household purchasing power is now mostly geared towards buying first necessity goods. As a result, vulnerability has increased in every industry the world over and in the wake of the post-Covid business environment has suddenly become strained.

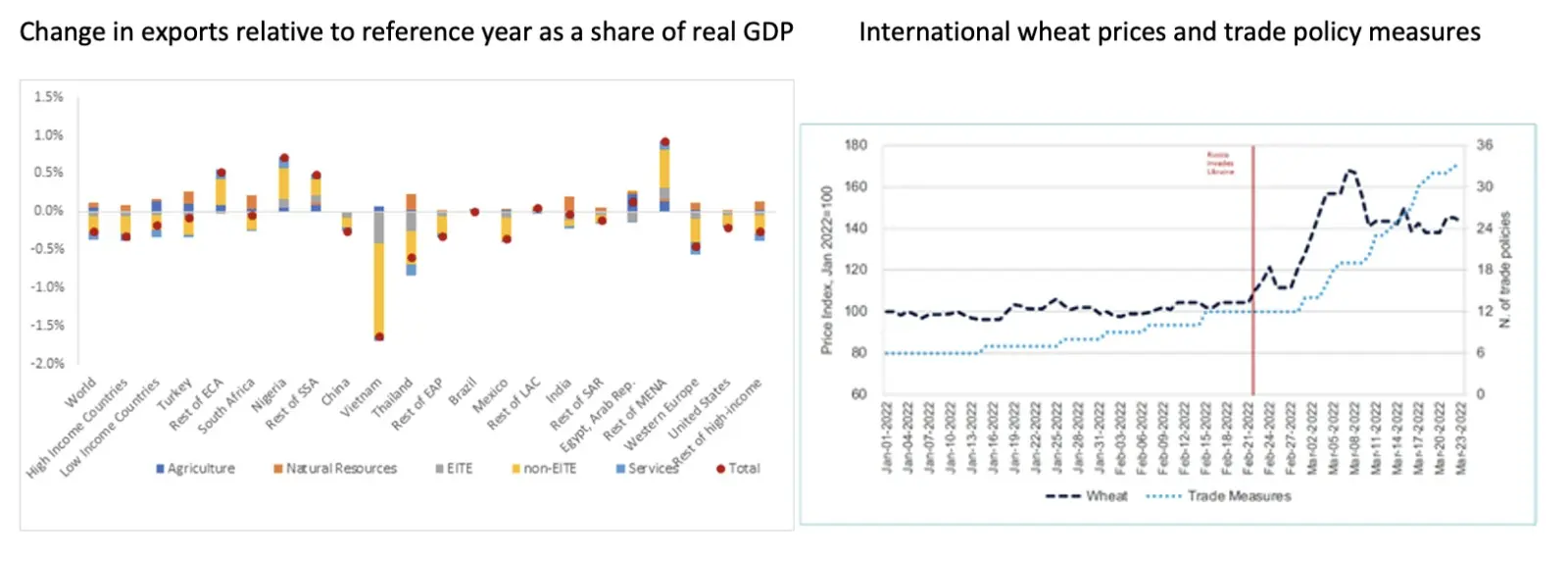

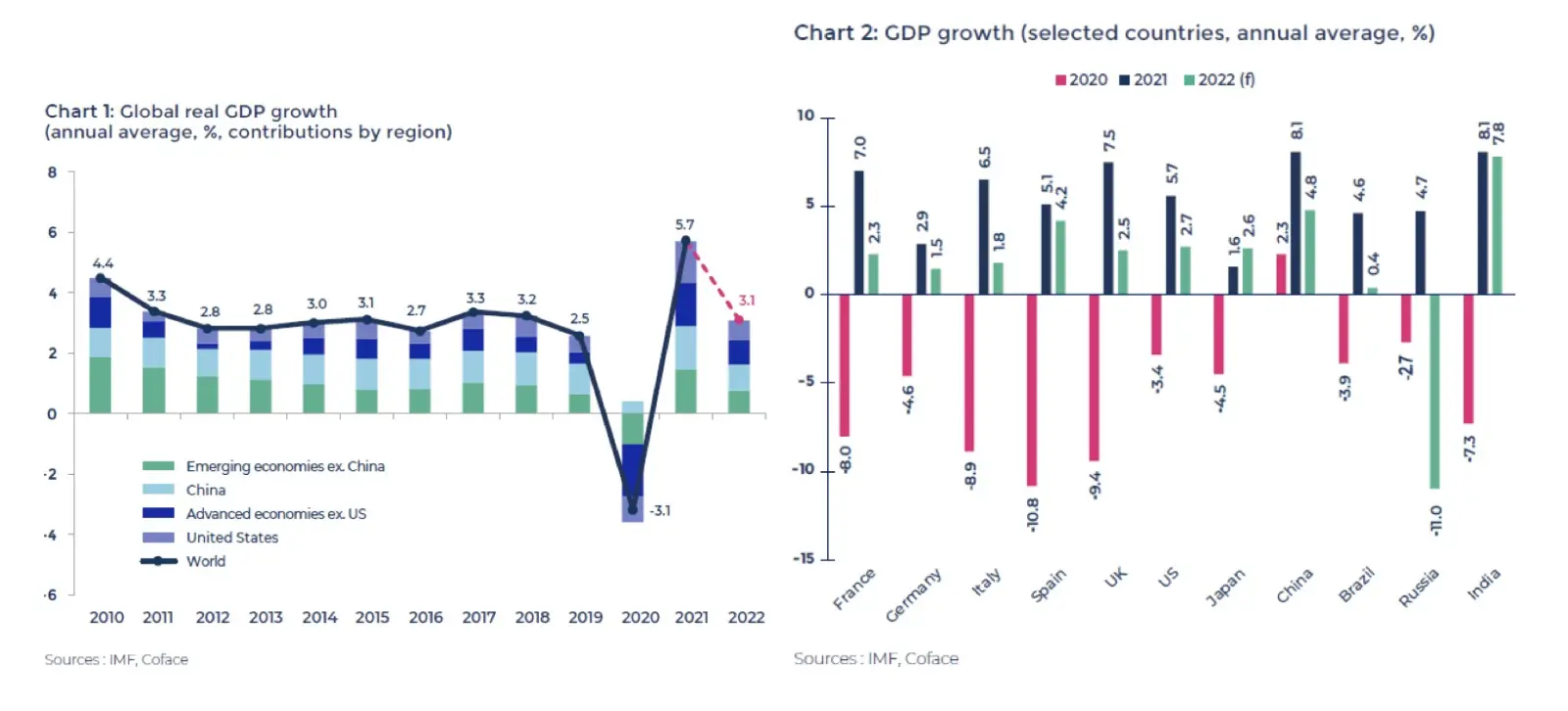

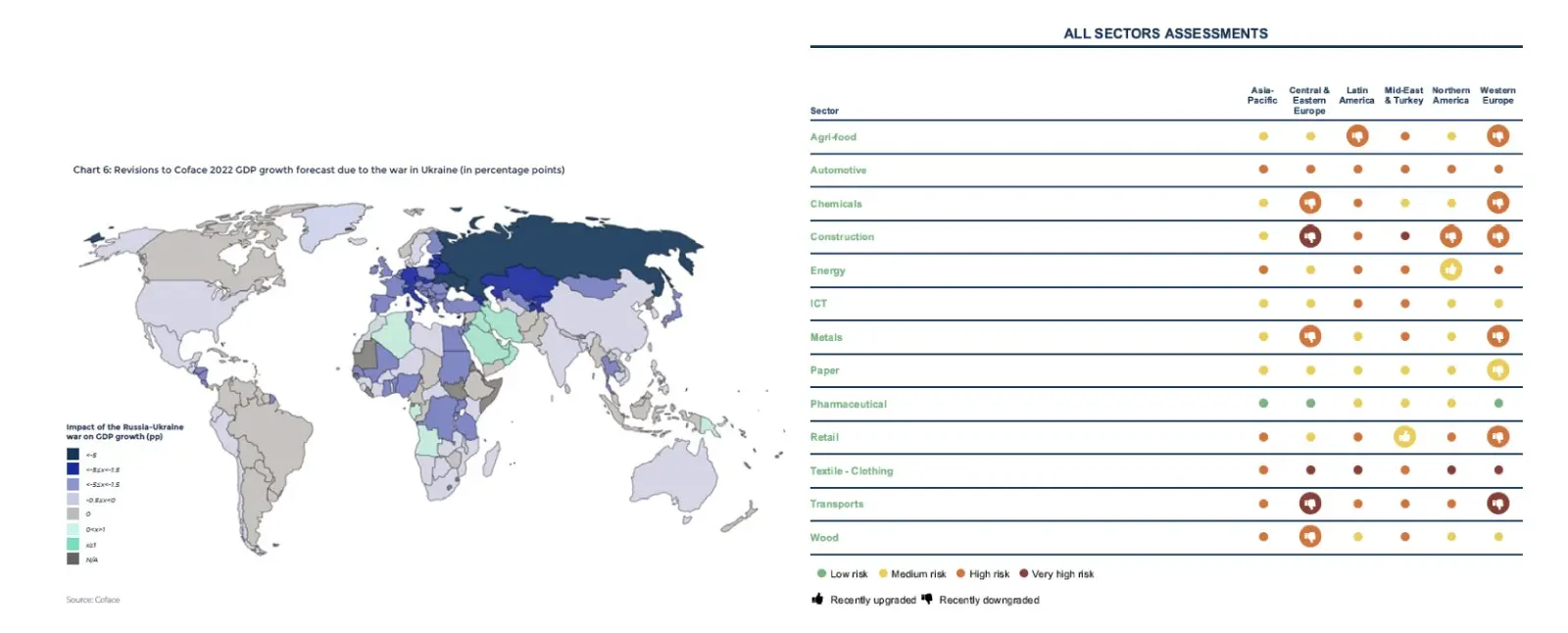

The diagnosis has been made by Michele Ruta, Trade and Competitiveness Global Practice economist of the World Bank Group, who just a week after the Russian invasion was already pointing out that the volume of business trades and global GDP had already dropped one percentage point, given the massive fall in net exports of manufactured goods in Vietnam, Thailand and Mexico, and in food sales not only from Ukraine, but also from Turkey, Brazil and India, and of fossil fuels in Nigeria and markets in the Middle East. This took place in the midst of a wave of convulsions in the global economy channelled into five conduits: commodities, logistics networks, value chains, foreign direct investment and sectors particularly sensitive to the new war-induced shockwave, such as tourism.

Since then, over a million companies have abandoned Russia. This is a commendable measure to lend credibility and effectiveness to the sanctions against the Kremlin, but we should not forget that tens of thousands of Western companies have benefited from the advantages of a globalised order. As it offers lower production costs in markets such as India, a wide range of consumers in China or access to mineral extraction processes in Africa or Latin America, while US and European banks provided them with regular loans or financial backing for their outsourcing strategies.

The mass exodus of companies leads us to think that the world has indeed changed, explains Michael Posner, a renowned psychologist and researcher of human behaviour who, on his Twitter account, emphasises that the world is going through a “critical moment in modern history”, with this manoeuvre by Vladimir Putin to re-establish the rules of the international geopolitical game, as among his first measures he has forced a change in business strategies; above all, for those of the foreign sector. Professors David Simchi-Levi and Pierre Haren support Posner’s theory and, in a joint Harvard Business Review essay, argue that the aftershock of the tsunami on production and supply chains, which has strained everything from the food to the semiconductors trade, has triggered an eagerness to go back to regional operational and manufacturing centres with a global stamp, something which was being discussed even before Covid-19 in the engine room of many multinationals due to the tariff war unleashed by the US and backed by China.

Europe’s energy dependency decrease is simply the retraction of business’ production submissiveness. Or, to put it another way, the Western private sector is seriously and urgently considering redirecting its outsourcing and offshoring strategies, which were implemented in the nineties to decrease costs and retain or increase competitive advantages. Regardless of the fact that this was an inescapable option since the 2008 credit crunch already. According to these scholars, the alternative is now imperative, since their exposure to risk is greater with the current tactic of outsourcing their services and because, to make matters worse, their local demands are not being met. Simchi-Levi and Haren prove this point using data. Between 2014 and 2018, Chinese manufacturing grew by 21%, while US manufacturing grew by 13%. And in 2019, the year before the Covid-19 pandemic, the Asian giant accounted for 28.7% of all global manufacturing, compared to the 16.8% produced by the industry of the world’s largest market.

Simchi-Levi, Professor of Engineering Systems at MIT in Massachusetts and director of the MIT Data Science Lab, and Haren, CEO of Fintech Causality Link, also provide another basic reading: In January 2020, a survey of 3,000 global firms found that the tariff conflict between Washington and Beijing had already prompted a review of their outsourcing tactics and the value chains located in markets with geopolitical risks. At least, a significant part of its productive processes. More than half of the US companies in more than 50% of the sectors have already declared their intention to restore their structures in order to relocate them to their home markets. In their view, this is not a regression of globalisation, but a fully fledged strategic adjustment until the course of the global order is certain. Schneider Electric, for example, has decided to build 3 factories in the country, one of which has already been planned for El Paso (Texas), and to establish 13 of its manufacturing centres for electric battery vehicles in the USA.

Also, regulations such as the US CHIPS Act or the European version thereof with the same name represent government efforts to reduce the dependence of the two commercial powers on their semiconductor imports from Taiwan or South Korea, despite being preferential markets and allied nations. Or their massive infrastructure plans, whose investments are once again operating in their economies with ample resources and investments in companies that, without these state funds, would have channelled part of their efforts abroad.

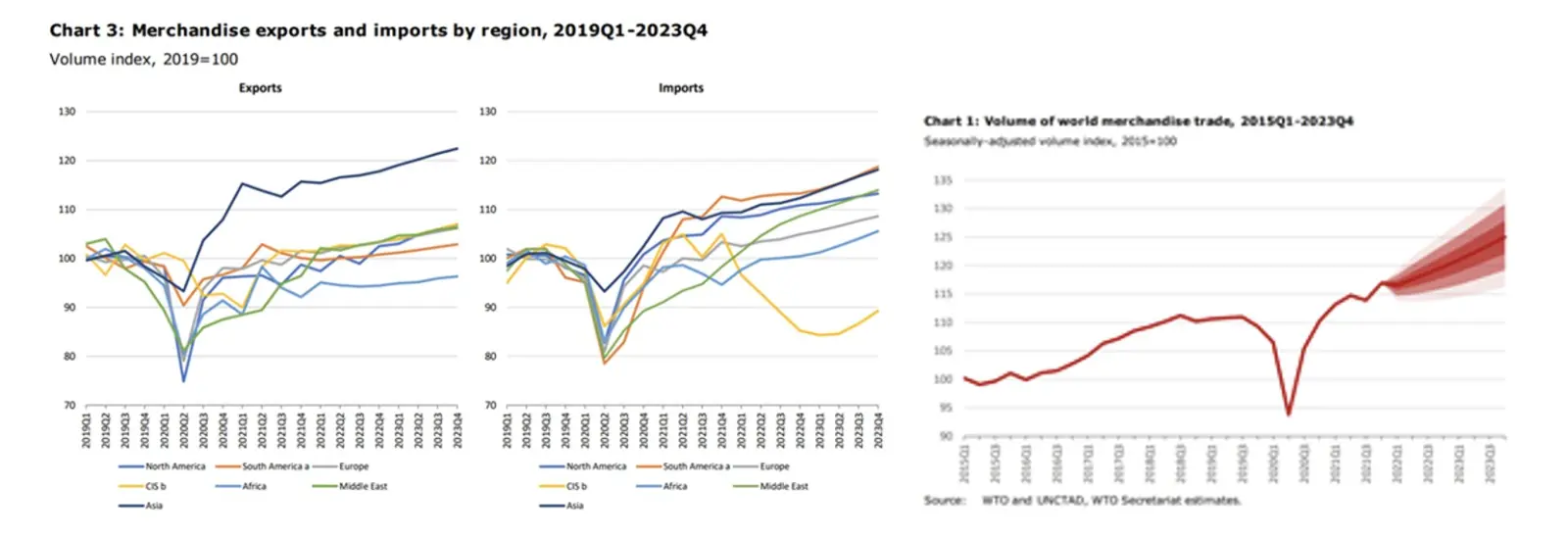

The warning has also been issued by the WTO. The highest institution of global trade has cut back on its forecasts on the transit of goods and services and has called on governments to take “measures to stimulate trade.” In its 2022-2023 Trade Forecast, the WTO attributes the impairment to the collateral damage from the war in Ukraine, which will reduce growth in international trade flows from 4.7% to 3% this year. In multilateralism jargon, an increase of 3% or less is a clear sign of a global recession.

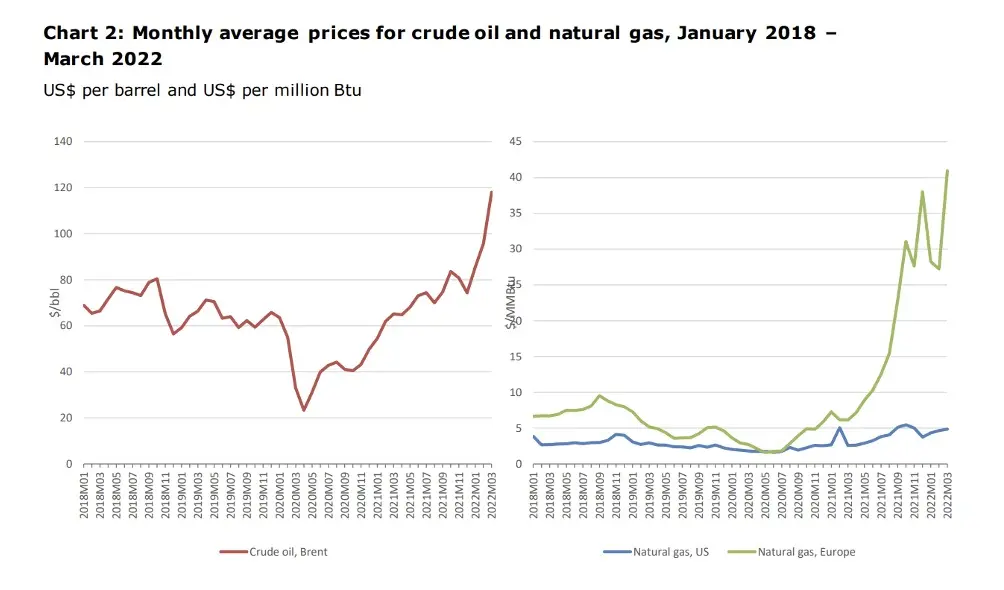

Gas prices have varied depending on the regions. However, in Europe they rose by 45% between January and March to $41 per million British Thermal Units (BTU), its universal measure, although in the US they remained at around $4.9. “The revaluation of energy has created upheaval in the global economy, with a more than notable impact on Europe,” admits the WTO, which emphasises that commercial services were directly affected by the aftermath of the armed conflict and, indirectly, by the rise in maritime, air and land transport prices.

More than half of the American companies in over 50% of the sectors declared as early as 2020, one month before the outbreak of Covid-19, their intention to restore their structures to relocate them to their domestic markets; this is not a regression of globalisation, but rather a full-blown strategic adjustment, experts warn

Reordering foreign companies

In this context, the remodelling and restructuring of international business lines appears to be an imperative. Rachel Barton, Head of Strategy Leadership for Europe at Accenture, believes that executives must prioritise the resilience of their businesses to ensure the future of their organisations, clients and workers alike. “There are no specific niches, but they do exist and the search for opportunities is latent,” although the volatility of the markets and the rising cost of financing also make them “volatile.” Contingency plans must be constant, as well as the “identification of potential actions” to guarantee the effectiveness of their foreign strategies. Because even before the war in Ukraine, seven out of ten managers had already expressed their utmost concern about spiralling inflation and interest rate hikes, which will impact the profitability and earnings of their companies and increase wage pressure, as well as reduce their ability to retain their workers.

For Barton, in this period of uncertainty, companies must control the impact of the rising cost of raw materials, the changes in consumer confidence indices and their investment plans, in the face of an immediate future with energy disruptions due to embargoes and geopolitical tensions over gas and oil, cuts in household spending on non-essential products and focusing their efforts on measures aimed at improving the efficiency of their operating systems. Given the real risk of stagflation or recession in certain markets with more or less direct consequences for certain sectors. And the imminent execution of a list of quick responses, including strengthening their short-term solvency lines, their operational training mechanisms, their supply chain management or human resources. “Predictability must be a constant” when deciding on scenarios with potential geopolitical risks, as their “exposure” to specific markets or sectors may result in a financial impact that “destabilises their assets” or affects the financial facilities of banks, the guarantees of supplier delivery or investor confidence.

McKinsey warns of twelve disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine, one of which is security in energy and food supply, as well as fertilisers and metallic products and minerals; in a full-scale revaluation of almost all raw materials, which already recorded a record year in 2021. With catastrophic estimates, such as those anticipated by the United Nations, indicating that the global cereal harvest could drop by 30% to 40% in autumn due to fertiliser issues. In a scenario where the FAO does not rule out, with its Food Price Indicator, that prices could rise by 45% in 2022, according to its worst predictive scenario, pushing millions of middle- and low-income people into poverty. With potential ramifications ranging from a hard landing for trade to currency depreciation or the unsustainable maturity of its debts.

Amid a diversification of global energy demands and a reconversion of value chains: 60% of the executive surveys agree that their companies are increasing their inventories of critical products; particularly, raw materials, McKinsey highlights.

Marc Saxer, head of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Asia and an international expert, emphasises the changing world order due to the transformations and paradigm shifts taking place in energy, production and distribution and in financial systems due to the war in Ukraine and the double challenge posed by Russia and China to the Pax Americana, which leaves the influence and power zones of the three superpowers, as well as the multilateral-liberal model, unresolved. All within a scenario of permanent geostrategic confrontation that drives the acceleration of capital exodus to industrial and technological transit and the resurgence of fossil fuel power in the post-Covid business cycle.

Saxer also recalls that since the 2008 credit crunch, “neither trade nor cross-border investment has fully recovered”, which has led to the Covid pandemic creating “more vulnerabilities in value chains.” And that the dominance of the dollar has come under scrutiny since the activation of the CIPS payment transfer system as an alternative to the Western SWIFT, which was blocked for made-in-Russia operations in the economic sanctions plan against the Kremlin, promoted by China, which is also accelerating the introduction of the digital yuan. Meanwhile, the greenback’s position within central bank foreign exchange reserves, in financial markets or in flows of some global trade commodities is declining. Beijing hopes that the sanctions against Russia will serve as an opportunity to challenge the dollar’s supremacy.

At the IMF, it is said that the armed conflict is reverberating through the corporate and industrial sectors across the global production map. Alfred Kammer, the IMF’s Director for Europe, breaks down the triple impact that, in his opinion, has emerged from the invasion of Ukraine. Through a surge in inflation driven by energy and food that has eroded incomes and reduced demand; a disruption in trade, value chains and international remittances; and a loss of business confidence due to the investment uncertainty over assets with specific weights in the capital markets, such as technology, and the flight of funds from emerging markets. All of this “has reverberated risks across the globe and created insecurity in supplies,” as well as a “drastic slowdown in trade flows and the world economy.”

In the long term, these changes should be refocused through reconfigurations of production chains, defragmentation of payment systems, channelling of energy and realignment of foreign exchange reserves and debt maturities. If we are to prevent globalisation from breaking apart and, especially, two of its associated elements, trade and technology. In Europe, governments will have to address their fiscal pressures once again to meet energy security and Defence spending requirements, and their companies and banks will “review their levels of exposure to Russia. In Central Asia and the Caucasus, countries neighbouring Moscow will experience the effects of the Russian recession and Western retaliation on their payment models, trade links, remittances, investments or tourist flows, which could have adverse consequences for their economies, inflation rates and current and budget balances.

In the Middle East and North Africa, energy and food price pressures and higher financing conditions are putting markets such as Egypt in a tight spot, as it imports 80% of its wheat from Russia and Ukraine. In an area where any increase in official subsidies will weaken its fiscal position in a climate of costly financing conditions that could fuel capital flight, raise debt levels and worsen its access to international markets. In sub-Saharan Africa, the problem is the halt in its prosperity programmes, with potential declines in tourism, vulnerabilities in its debt services and a higher degree of social and corporate confrontation, as its nations import around 85% of their wheat from the two countries involved in the armed conflict, “at exorbitant prices.”

In Latin America, inflation has risen above 8% annually in five of its largest economies: Brazil, Mexico, Chile, Colombia and Peru, with their central banks fighting to maintain their credibility in the battle against spiralling prices. And a disparate effect on commodity prices, which is affecting Central American countries, importers of gas and oil, especially the Caribbean nations, while oil, copper, iron and corn and wheat or metal product exporters will be able to mitigate its impact on growth. In an environment with still feasible financial conditions, but dependent on future rate hikes in a Federal Reserve area of influence.

In the Asia-Pacific region, the IMF explains the limited damage due to the strengthening of free trade areas with increasing economic, financial and investment ties. Although the most harmful effects will focus on ASEAN partners, oil importers, and India and the Pacific island economies. China will suffer from less generous fiscal stimulus programmes aimed at boosting growth around 5.5% of GDP this year, as well as from a slowdown in demand for its exports. In South Korea and Japan, fuel subsidies for the population and companies may cushion the impact for some time, while in India, the CPI is already at the upper limit of the range set by its central bank.

The IMF calls for new fiscal expenditures to address this inflationary spiral and stresses the great importance of global and regional safety nets. “We live in a world with a higher propensity for shocks,” explains the IMF’s Managing Director, Kristalina Georgieva, who highlights the need for “strengthened concerted collective action to try to avoid their effects.”

Oliver Jones, from EY Global’s Sustainability Area, considers that business models with an international vocation will persist in the emerging economic order but that they will have to adapt to the new geopolitical realities following the seismic shift the war in Ukraine has caused in the foundations of globalisation. “Executives and managers will need to closely monitor business alliances, the geostrategic context and the socio-economic considerations” of the markets where they establish their businesses. “CEOs need to understand the dynamics to shape strategies and manage all political risks,” he explains. And “it is imperative that they do so,” he clarifies.

In the emerging multipolar world, with the possibility of a decoupling into two rival and antagonistic trade blocs, companies “may see increased government intervention in their value chains, restrictions or outright bans on certain cross-border investment flows, export controls, restrictive trade measures and more intense regulatory scrutiny. Hence, the essential recommendation is to align investments towards markets under free trade agreements that operate on the same wavelength as the standards of each key bloc to which their country of origin belongs, and that opt for digitisation, manufacturing cooperation and commercial sales plans. A landscape that EY experts believe will be particularly challenging in sectors strategic for national security, such as semiconductors, IT and telecommunications equipment, electric vehicles, pharmaceuticals or certain critical infrastructures. In a framework where advances in sustainability and energy neutrality will continue to govern business models and product portfolios.

According to EY, in the short term, sanctions and the war will increase fossil fuel demand to meet the needs of businesses and households, which will raise revenue for companies and producing countries, who will gain geopolitical influence, while in the medium and long term, the energy transition will accelerate with more urgent measures to diversify sources that ensure sustainability and decarbonisation. With caution regarding green minerals, which are essential to support the transition, with Russia monopolising 11% of the global nickel rate and 5% of the cobalt rate, which gives Moscow more leverage to exacerbate global supplies. Companies and governments will need to innovate in their value chains by including joint ventures with mining companies or circular economy initiatives to recycle, for example, electronic materials containing these components.

The management of these geopolitical risks requires constantly adapting to their effects and real-time analysis of each variable to incorporate them into each business protocol (or ERM for its acronym in English); establishing a cross-functional geostrategic team that sets objectives and analysis skills over business units, with the ability to update the regulatory effects that may arise and to constantly refine the strategy according to the requirements of geopolitical reality, with the purpose of planning processes, especially in the value chains and market entries – or consolidation tactics – in foreign markets.

The war in Ukraine and sanctions on Russia have heightened the importance of understanding geopolitical dynamics and adapting them to corporate risk management (ERM), so executives will need to carefully assess their effects on value chains or the company’s operational strategy in the new global order

Time to diversify risks and markets with extreme caution

The Spanish Export Credit Insurance Company (Cesce) has just reviewed the consequences of the war on the internationalisation process of the Spanish economy, in which its president, Fernando Salazar, recently pointed out that, for the time being, foreign trade with countries not involved in the conflict has not been slowed down. In his opinion, the new geopolitical order “is setting the international agenda and political risk coverage is key in this scenario.” It is not – he clarifies – the desired atmosphere, but the armed conflict “will bring niches such as the geographical proximity of value chains or bets on renewable energies and national energy production.” Salazar spoke at the webinar organised by the Exporters’ Club and Iberglobal, Implications for Spanish Internationalisation of the War in Ukraine, in which he shared views and analysis with José María Viñals, partner for international trade and economic sanctions at Squire Patton Boggs, and with Alfonso Tena, head of Institutional Relations at Indra. The three speakers agreed that “no collateral effects related to exports and imports with other markets” are being perceived after the first one hundred days of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Although it has obviously had direct and immediate effects. Because the volume of Spain’s trade with Russia, Ukraine and Belarus amounted to 10 billion euros. Furthermore, and immediately, indirect repercussions have arisen, such as the rise in commodity prices or complications in terms of land, sea and air logistics, which affect international trade but which, until the middle of the second quarter, “are not hindering or paralysing it.” Regarding geopolitical risks, the president of Cesce was blunt: “geopolitics is setting the international agenda and the world is changing, shifting from a US hegemony to a multipolar scenario where China has gained increasing weight.” In light of this reality, companies must take into account – he explained – the existing high risks and protect themselves with political risk coverage. He clarified that policies “do not cover fines imposed on sanctioned companies.” Even if it is known in advance that the operation is sanctioned, it would be excluded from coverage. However, he explained, it could cover “previous operations that cannot be carried out because the other party is affected by these sanctions.” In this case, if our client could not collect on the transaction, the State-backed insurance would cover that transaction, he noted.

In terms of opportunities, the diagnosis was shared. The new world will tend to shorten value chains, bringing and diversifying production, even if it proves to be somewhat more costly, and businesses will emerge from the shortages in supply networks; renewable energies and national energy production will be decisively promoted to correct Europe’s energy dependency; companies will focus on diversifying their foreign trade beyond traditional markets; many countries’ defence budgets will increase, a sector in which Spain is strong and will bring along other segments, such as electronics or telecommunications, and, in general, caution and thorough geopolitical and economic-financial analysis of the geographical destinations they plan to go to will be necessary.

One of the latest assessments by Coface emphasises that the economic shift will generate many losers and very select winners. With European partners at the epicentre of the tsunami due to their energy dependence on Russia, and most of the emerging circuit experiencing capital outflows or fighting pressure to devalue their currencies and avoid worsening their current account and debt balances. Under the belief that “the world has changed, and nothing will ever be the same again.” With a strong reaction from the Federal Reserve to the inflationary jump in its economy, which “will cool activity more than expected,” African countries in a state of permanent struggle against commercial and logistical bottlenecks, political risks and rising financial conditions, awaiting China’s revival in the second half of the year, Latin America under a still uncertain net impact but not without the risk that gradual worsening will trigger social unrest and the Gulf economies as the major winners of the conflict.

Meanwhile, Crédito y Caución has gone from selecting Uruguay, Ivory Coast, Israel, Qatar and Taiwan as the markets best positioned to recover growth and offer business opportunities in 2022 at the start of the armed conflict to insisting that insolvencies grew 2.2% in 2022, with very significant increases in automotive (220%), extractive industry (75%), primary sector (75%), food (46%), transport (33%), retail (30%) and construction (29%), and that only 20% of companies have commercial risk departments, despite the tragic odyssey in the wake of the 2008 crisis.

As a result, the creation of structures to systematically control business are at the least risking dealing with the changing global order, in which, they say, globalisation will not disappear, but new challenges in value chains will emerge. With Latin America growing sluggishly again, Europe approaching stagflation, the global economy in decline and sharp increases in insolvencies resulting from the withdrawal of stimulus and the bankruptcy of zombie companies across the world. And giving short, medium and long term returns to the pharmaceutical industry – as well as the energy and military industries, in addition to fund managers’ boards – with low levels of global credit risk and prospects of rising demand for drugs in both developed and emerging markets.

In the first 100 days of the war and with inflation as the declared public enemy number one, market and sector business niches have been obscured by the global order shift and financial deterioration caused by interest rate hikes, which impair risk diversification strategies